- Home

- Dora Drivas-Avramis

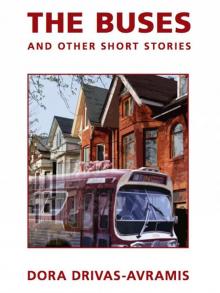

The Buses and Other Short Stories

The Buses and Other Short Stories Read online

Copyright © Dora Drivas-Avramis 2015.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, by any method, without the prior written consent of the author.

ISBN 978-09940127-0-8 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-9940127-1-5 (ePub)

ISBN 978-09940127-3-9 (Kindle)

To my parents Marika and Demitrios Drivas

And to all the thousands of Greeks, who crossed the Atlantic with meagre possessions but plenty of dreams, to embrace the young nation of Canada and enrich it with their quiet contributions.

The Buses

Theodore’s Homecoming

Making the Old New Again

Sunset Years

Fatal News

Something Greater Than Love

At George’s Barbershop

No Price So High

The Missing Cross

Misplaced Duty

Divided Loyalties

Double Heartache

First Impressions

The All White Road

The Buses

Alone, at ten every morning he sat on the white wooden chair on his grey veranda and counted the buses going by on Pape Avenue. Every five minutes the northbound bus appeared and then the southbound, one, two, three…twenty, twenty-one…Some buses were empty; others, packed, and he tried to estimate the number of passengers. But he lost his concentration. Sometimes, the drivers’ skill with the wheel grabbed his attention, and his thoughts strayed. Was it twenty-eight or twenty-nine that passed by? He couldn’t remember and he’d start counting all over again until noon. Then he stood, his lanky frame leaning to the side like a tall cypress tree against the wind; he rubbed his bristly beard with his left hand, adjusted his dark-rimmed glasses, and went indoors either to rest or prepare a sandwich for himself.

The next morning, exactly at ten, in his wrinkled black trousers and stained tan sweater, he dragged his tattered slippers bit by bit, stepped onto his veranda again and inhaled the heady fragrance of the lilac tree. Then, he lowered his body and dropped back into his white chair with a look of weariness; he appeared fagged and sallow like the day. As usual he waited to see a bus going by, so he could start counting every five minutes from both directions. If he missed the first one or subsequent ones, it was because the people on the sidewalk distracted him—a young man walking with a handsome dog, a child waving to him from the stroller as his mother pushed it hurriedly or just groups of shoppers from the nearby supermarket who ceaselessly streamed by with their perspiring faces. Once he started the counting and did it for awhile, he placed his hand on his forehead, rubbed his temple and wondered where he left off. It wasn’t easy, but he tried to concentrate on his counting. In between the passing of the buses, he spent the time looking up and down Pape Avenue and admired the tall maple trees here and there; he also noticed the swirls of dust in the cracks of the pavement, and the rubbish that had collected in the gutters. Occasionally, he came up with a ball park figure on the number of passengers in some buses and around noon he’d say, ‘tomorrow again.’ And these words were the farewell and the promise that he’d continue the counting tomorrow.

Formerly, his wife Grace sat calmly in the empty white chair beside him. A petite woman, dun-haired, she admired her colourful tulips, crocuses, peonies, and looked at them intensely as if she was seeing them for the last time. “Ah! Our beautiful flowers, aren’t they lovely, Vasili?” or “Vasili look at that lovely little girl in her white dress and navy sandals, isn’t she gorgeous?” She smiled at everything and everyone and didn’t expect a response from Vasili. Loyal and loving, for forty-five years she was like this with him—a lifetime of unbroken habit prevailed between them. Grace sat faithfully beside him, kept him company, his shadow who rarely heard a word from him.

Her freshness and malleability hooked him from the moment they met on the Queen Frederica ocean liner on their way to Canada from Greece, when she was still at the age when the flexible soul offers itself to the first grasp. And that grasp was Vasili. And she still worshiped him. Occasionally, though, besides the adoration expressed in her plaintive eyes there was a mixture of unease that bordered on fear which seemed to be asking, ‘why don’t you talk to me?’ But she never uttered it, and had accepted this reality with a humourous fatalism. She hoped that some day he’d talk to her and reveal his anxieties.

Calm, close, devoted; she was the one who had first noticed the buses. “Isn’t it strange?” she asked. “Every five minutes they go by in a synchronized way, like clocks which never stop ticking. Some buses are quite full, the passengers resemble packed sardines. Look at that bus, how many people do you suppose are inside, Vasili?” But he never noticed the bus or its passengers.

Now she was gone. A silence reigned. And he remembered… Her image consumed him. It had happened about three months ago, quietly, suddenly and unexpectedly, the day before the celebration of their forty-fifth wedding anniversary. Their two daughters, who had planned the event, had briefed them on the details. It was to be a quiet affair, nothing fancy, a dinner party at a Toronto local restaurant, with just the family and a few close friends, who would come to congratulate them and wish them Chronia Polla, many years and Na ta ekatostisete, may you live one hundred years together.

Vasili vividly recalled her gaiety on that day, her smile and the light in her grey eyes. She placed some bracelets on her left hand and wondered which one would be appropriate for tomorrow’s special occasion; then, held the pearl and diamond earrings against her ear. One after another she tried on the dresses she’d wear, the black satin, then the grey and cinnamon, but couldn’t make up her mind. She was hoping he would help her choose one; she looked at him and waited. Vasili’s apparent disdain for her appearance did not irritate her, for he was always withdrawn.

Around three in the afternoon, she excused herself and went in their bedroom for her nap. She never returned. Still and serene, they found her in the middle of the bed. “Not possible!” “Why?” “But she was not in pain, never sick!” Vasili’s hand started shaking, then his whole body trembled and he fell on his knees. “Why, my Grace?” Her heart simply stopped ticking, according to the doctor. Family and friends came to pay their respects. Instead of Chronia Polla, they shook Vasili’s hand, hugged him, pressed cheeks and said, Eonia e mnimi, “Everlasting, the memory,” “My condolences,” “Remember her.”

Different incidents in various settings floated in his mind. Thoughts bubbled up perpetually from the black springs of his hidden misery, they blotted out the light of day; whichever way he turned his thoughts, Grace’s face appeared. She pressed his clothes, sat by him, slept beside him and smiled at him. She served his dinner and straightened his tie…

Suddenly a familiar voice interrupted his thoughts: “Hi Kyrie Vasili.” A pleasant youth, about twenty, with dark features, wearing jeans and a blue sports jacket, rested his arms on the sloping divider of the two verandas. “Nice to see you again, how are you, sir?”

“How am…, Who…?” To see clearly, Vasili placed his right hand above his grey bushy eyebrows, and turned his head.

“It’s me, sir, Andrea, your neighbour’s son.”

“Andrea! My dear boy,” the old gentleman welcomed him warmly. Gradually, he rose, steadied himself on the veranda’s wooden white railing and slowly stepped closer towards the young man.

“Finished your studies my boy?” and he reached out and clasped both Andrea’s hands.

“I finished my exams, and have a couple years left for my degree. I’ll work here in Toronto during the summer months and return to Vancouver in September, I…” Abruptly, Vasili interrupted Andrea by lifting his wrinkled hand entreati

ng the young man to wait. He turned his head towards the road and said, “Another one went by, that will be number nineteen or twenty…”

“What do you mean Kyrie Vasili, nineteen… what?”

“The buses dear boy, the buses going by, I’ve been counting them…” An awkward silence ensued. The older gentlemen noticed the young man’s perplexity, and he broke the stillness: “She used to count the buses and between them she usually said something, something insignificant in her calm voice and with that sadness in her eyes. It’s strange, in her eyes the buses passed by and I had never noticed them. Do you know what I mean Andrea?”

“Not exactly, Kyrie Vasili,” Andrea answered in a hushed voice. And he continued, “are you referring to Kyria Grace?”

“Yes, my dear wife, the blessed one.” And after a few serene seconds, two tears rolled down Vasili’s white cheeks.

“I’m so sorry for your loss sir. She was a wonderful person, more like my second yiayia than my neighbour. I’ll always remember her kindness and helpfulness, even my siblings considered her their second granny.”

“Thank you Andrea, you’re a good lad and your parents must be very proud of you.”

The uneasy tranquility between them continued. Andrea drummed his fingers on the wooden divider and then he asked with hesitation: “Excuse me for asking sir, but why did Kyria Grace count the buses? I…I mean why did she care about the number of buses? On hearing this, the older gentleman lowered his head and quickly covered his eyes with his left hand; his hushed sobs shook his upper body and a leaden sense of failure overcame him. For the life of him he did not know how to answer Andrea’s question: he could only sob as the great surges of loneliness broke over him and he tasted all its accumulated bitterness.

“I’m truly sorry, sir, I didn’t mean to…” But old Vasili placed his intricately-veined old hand on Andrea’s and said, “please, please, young man no need to apologize…” Still, he did not know what to say to Andrea. But when he noticed the young man’s glance fall on the suitcase beside him and he showed a desire to go indoors, Vasili clasped his hand tighter indicating a need to continue their chat. And suddenly, he blurted out: “I never talked to her. On many occasions, I never talked to her for hours; I was thinking. And she wanted to converse, she yearned to hear something, wanted to talk to someone and this is why she counted the buses, do you see now? I must do the same now that she’s gone; it’s fitting that I do the same because there’s no one for me to talk to, for she’s not here; there’s no one. And only the buses go by on time, every five minutes and I’m counting them for hours and I could count them for days and nights, because she loved the buses. Oh… what am I saying… she did not love them, she counted them, because I was silent and now I’m counting them for her, and I know what it means …, how it feels when there’s no one to talk to you, when there’s no one to answer your questions. Does it make sense to you now, dear boy?”

No, the young man did not understand it; he was hopelessly confused and uncomfortable, but he couldn’t say that out loud. And when old Vasili saw the bewilderment in young Andrea’s grey eyes, he helped him out, “that’s all right my boy; it’s a puzzling matter. You go on in now. Your parents must be anxious to see you.” Andrea pressed his hands into the old gentleman’s and headed indoors. Heavy-hearted, Vasili turned and tried to remember the number of buses that had gone by and he couldn’t. “Enough for today,” he said. And slowly and unsteadily, he too headed indoors and thought that Grace was much better at counting the buses, more exact; and she appeared to be searching for something, waiting for something. He did not know what it was, exactly, but he was determined to keep on counting until he found it. In the meantime, his regret was too painful and raw for having missed the chance to ask her, ‘why the buses in particular, Grace? Why?’ He would keep on counting.

Theodore’s Homecoming

The taxi, a black Mercedes, crawled across the endless mountains under Greece’s burning sun in Southern Peloponnese, the hand of land that waggles its fingers in the Aegean Sea. The driver, whose dark, weather-beaten face was partially covered with his sunglasses, minded the abrupt turns around the mountains. Enjoying the air-conditioning in the back seat, the only passenger Theodore Stamkos, in his late twenties, with his dark shoulder-length hair, wore a spiffy bell-bottomed brown suit, with a gold maple leaf on his lapel, and polished brown loafers. He admired the hills and the rampant oleanders, wild with scent and in all sorts of colours, blossoming on either side of the road. The far-off mountains like a dark faded line that touched the sky gave Theodore a sense of the boundary; he thought: ‘behind that mountain chain lies Plitra Beach, the sea coast village where I was born.’ He noticed the road sign indicating Molae, 25 kilometres; Plitra was 16 kilometres south of Molae and he estimated that in about twenty-five minutes he’d admire Plitra Beach up close.

The peaks of the mountains, the ravines and precipices captivated Theodore. The red, yellow and white rocks, whose hue changed depending on the weather, moved him; he remembered his Papou telling him that the mountains had a history, a history which you had to look closely to find its beginning. “Theodore, my boy, the mountains are like books, you open them and learn all kinds of things. You dig in one place and read: five, ten…twenty million years passed before this mountain sprouted up. In another spot, you find marble, somewhere else, gold, silver or a huge reservoir of cool water.” As a youngster, together with his grandfather, Theodore spent many hours exploring the mountains, which seemed to ask, “Do you want to learn my secrets? Have patience. Dig and read.” And the more the youngster poked about, the more mysterious the mountains became.

As he marveled at them now, his thoughts turned back, way back to the land’s magnificent myths and history. Wherever Theodore looked, he encountered evidence of Greece’s traditions, and an inexplicable blessedness enfolded him; he could spend hours gazing at the mountains, the multi-coloured fields and seashores. Enthused with the beauty around him, he was struck with how wonderfully the present mixed with the past. It was as if history, tradition and legend strolled hand in hand, and Theodore whispered, ‘what heavenly joy! I’ve come back. My roots are deep and strong here, my ten-year absence has not erased them.’

Theodore’s heart fluttered; he was returning to the homeland, which he had left like so many others, to try his luck in Canada. And the luck, thank the Lord, smiled on him. The first years he laboured and learned the hard way how difficult it was to earn a living and also put money aside. He worked at odd jobs in restaurants owned by fellow Greeks in Toronto. As much as he could, he lived frugally and shared a flat with two other bachelors who had come from his village. A penny-pincher and go-getter, he saved the required sum to buy, with his partner Pete, the Elmwood restaurant at the corner of Bloor Street and Dovercourt Road. It was hard at first, but with determination they attracted enough customers to make a good living. And this is why he decided to return to Greece, and planned to spend six whole months. He wanted to rest after working non-stop for ten years, and longed to see his parents and Greece again.

Nostalgia and rest were not the only reasons that brought him back though. Without wanting to admit it, one of the motives was this: to show his village the transformation during his time in Canada. His co-villagers remembered him as a poor lad who ploughed the fields and left one day with a small bundle and his fare for the Queen Frederica ocean liner, bought with borrowed money. No, he was not a vain person. Theodore smiled at the thought of how surprised his family, friends and the whole village would be with his manner of dress and cultured appearance. No one knew of his arrival. He wanted to surprise everybody; he longed to describe Canada’s beauty, from its polite people to its majestic trees, and from its wide roads to its magnificent skyscrapers. Intensely, he felt all these things, but what possessed him presently was the joy of his return.

The taxi passed Molae, built like a colossal amphitheater—its houses, from the base of the Kourkoula Mountain climbed upward like rungs of a ladder on

e above the other as far as the eye could see. The road ahead was straight and shimmering, like a rolled-out silver ribbon with the burning light on the pavement. Theodore lowered the window and breathed deeply the clean air with its heady fragrance of oregano and thyme. The sun had reached the centre of the clear blue sky, and he noticed a flock of seagulls with their wings outstretched to the limit, as they soared. In the groves in the hollows of the hills, the cicadas sang madly. ‘Canada had everything’ thought Theodore, ‘yes, absolutely everything, but it couldn’t match this country’s beauty.’

With an aching feeling, he remembered his youthful years, his first love which had remained with him like a tattoo, a permanent mark on his left arm, his lifetime vaccine. It was painful to visualize Maria’s oval dark face, her long hair, her sweet chestnut eyes, and her bashfulness. Would she still be there? Again and again he remembered his friends, their beach parties, their fishing expeditions and the jovial times they had. How would his inseparable school friend Michael react when they would meet shortly? Theodore imagined his surprise. He constructed in his mind the image of Plitra, as he remembered it, and the loving faces of his dear friends.

The ever-present white chapels and shrines, the olive, orange and fig groves, and the endless rows of cypress trees created the familiar landscape for Theodore. In a few minutes, the vehicle would approach his beloved village. “Step on it,” he commanded the driver, “I want to reach Plitra’s Agricultural Co-operative before it really gets hot. We’ll stop there for a few minutes.” The driver nodded in agreement and the vehicle’s engine thundered. Theodore remembered clearly the beautiful elongated building with its white stucco walls and green shutters; it was the commercial hub of the area with its significant agricultural activity. The bustle at the impressive co-operative, where the farmers brought their produce, flashed in multi-coloured pictures in Theodore’s thoughts. The place was full of commotion as farmers pulled up with their tractors, mules and donkeys pulling carts full of bins of figs and other products; they greeted each other and chatted about nothing and everything, made deals and haggled with the co-operative’s representatives. Their coaxing and argumentative voices rang in Theodore’s ears now. He couldn’t wait to meet some of them again. Would they recognize him?

The Buses and Other Short Stories

The Buses and Other Short Stories